[button style=” url=’https://karibu.org.za/wp-content/uploads/khanya-College-Journal-No-35-P37-39-From-the-Defeat-of-Apartheid-to-FeesMustFall.pdf’ target=’_blank’ icon=’icon-entypo-download’]PDF DOWNLOAD[/button]

From the Defeat of Apartheid to #FeesMustFall

The ANC-led government was elected into political office in 1994. Enshrined in the Reconstruction and Development Programme (RDP), one of the mandates of the ANC government was to deliver quality education to the working class majority. The constitutional right to education was granted in 1996 during the adoption of the final constitution of the Republic of South Africa. Since then the fundamental problem has been the fact that the government has been shifting funding problems from the state to working class parents who are also facing problems of unemployment and poverty. At the same time government policy has promoted the flourishing of private schools where children of rich parents are able to enjoy quality education.

The situation in schools has not improved. The ANC government has not met the demands and aspirations of the class of 1976. The School Register of Needs Survey, which was conducted by the Department of Education and Training in 2001 revealed the following problems in education.

- The number of paid educators had decreased to 23 642.

- Governing body appointments are made through additional fundraising initiatives by schools, which means the costs are shifted from the state to communities with the weight of the burden falling on low or non-income earners.

- Twenty-seven percent of schools had no running water.

- Forty-three percent of schools had no electricity.

- Of the 27 000 schools nationally, only 8 000 had flush sewers and 12 300 have pit latrines.

- Eighty percent of the schools do not have libraries.

- About 10 700 needed additional classrooms.

The government’s adoption of the Growth Economic and Redistribution (GEAR) policy in 1996 did not improve the situation in education because the policy put an emphasis on containing expenditure in education and called for an increased private sector involvement in public education. Instead of raising adequate revenue by taxing big business and increasing expenditure on education in such a way that redresses the imbalances in education and deals with the problems highlighted in the School Register of Needs Survey of 2001, government has tended to implement policies that favour big business.

In the mean time, education continues to be in crisis. Government argues that primary and secondary education is free but the reality is that working class parents, many of whom are unemployed, are forced to pay user-fees in schools. The same parents are also compelled to buy uniform for their children. There is always a shortage of teachers, textbooks and equipment in schools. There is also prevalence of HIV/AIDS in schools among students and sexual harassment of female students continues.

Higher education is becoming more and more inaccessible to students from working class communities. State funding of higher education as a proportion of GDP decreased from 0.79% in 1998 to 0.7% in 2004. As a proportion of the GDP state spending on higher education did not even begin to tackle the problems of access to higher education for working class students.

Students have been taking up campaigns for access to education from 1994 to 2015, although the struggles in this period have not been as generalised as the ones in 1976 and the 1980s period. Some of the important student organisations have declined dramatically. It is extremely difficult to talk of a student movement because of the fact that there is no conscious national force that is rallying and organising students to struggle for access to education. At the same time, there is no student-worker alliance as we used to know it in the 1980s.

However, some of the key struggles in the period 1994 to 2000 include:

- In February 1994 seven schools in the Springs area boycotted classes in protest against the arrests of certain COSAS members. The COSAS members had been arrested during the struggle for access to education in schools in the area.

- In 1995 a number of tertiary education students boycotted classes as part of the struggle against financial exclusions.

- In 1998 the universities of Fort Hare, Western Cape and Venda were closed down because of student protests against financial exclusions.

- In the scenes reminiscent of the turbulence of the 1980s, all seven schools in Balfour’s Siyathemba township (in Mpumalanga province) boycotted classes demanding free and compulsory education. In response to protests, police used force against the students.

- In 2000 over 10 000 students marched under COSAS’ banner demanding free and compulsory education. Throughout the 2000s, thousands of students in various institutions of higher learning all over the country engaged in constant and ongoing struggles against the rising cost of tertiary education, the financial exclusion of thousands as a result, poor accommodation, lack of access to food, racism, authoritarian university administrations, expensive and poor transport, and many other issues. These struggles in many cases were violently suppressed by the police and the university authorities, and many students were arrested or expelled from universities.

The institutions most affected by these problems and by these struggles were the historical “bush colleges”. As part of government policy these institutions were ‘merged’ with institutions that serviced relatively well-off middle class students who were predominantly white. These ‘mergers’ simply transferred the wealth gap between the bush colleges and the white universities from being a gap between institutions, to being a wealth gap within the same institution. In many of the struggles waged by students in this period therefore there was always an element of struggle against inequality.

Even with the mergers, however, the government did not dare to touch the really wealthy institutions such as the University of Cape Town, the University of the Witwatersrand, Stellenbosch and so on. Many black students from working class families were being admitted into these institutions in increasing numbers throughout the 2000s and the 2010s. The inequality in wealth between these students and their white counterparts were therefore stark, and these disparities were therefore reflected in students ability to complete their degrees or to pass on a consistent basis. Although they were located within rich institutions, these students lived a life similar to that of students in the bush colleges.

On the other hand, even those black students that came from middle class backgrounds were increasingly unable to keep up with rising fees, accommodation and a general increase in the cost of living as the economic crisis continued to deepen. The global financial crisis of 2008/9 triggered major pressures among the black middle classes. These included high real interest rates, the decline of the presence of blacks in the ownership of the economy both at the stock market level, and in the real economy. In addition to all this, the black middle class’ post-1994 honeymoon was over – they increasingly came face to face with the entrenched power of white monopoly interests in the country. As debt levels rose among this section of the population, many began to fall back into the working class, and most began to lead a precarious existence as middle class people, with the threat of dropping off into the working class remaining a real one.

A series of contradictions expressed and concentrated these developments over a period of time, but accelerated against the background of the global economic crisis and its (silent) effects on South Africa:

- Struggles against fee increases and financial exclusions had been ongoing for over a decade in the bush colleges.

- Post-2010 the economic crisis exerted enormous pressure on the middle class, so that for this strata fees became a serious issue as well.

- The state had adopted conservative macro-economic policies and was therefore unable to respond to the pressure that was building up in the university system for 20 years or more.

- The government of the African National Congress had steadily lost legitimacy in the eyes of the mass because of large-scale corruption and its failure to “open the doors of learning and culture”.

- Throughout the post-apartheid period – for reasons touched above – a culture of resistance and protest had been kept alive among the mass of the people. Unlike many post-independence situations, the ruling elite in South Africa did not have the authority to call on the people “to go beyond protest” and embrace “patriotism”, “nation-building”, “rainbow nation”, “social cohesion”, social compacts” and so on. All these are variations of strategies and ideological constructions that are used by new ruling elites to manage dissent.

- The historical signal that these attempts had all failed was the massacre of 34 miners by the ANC government at Marikana. With Marikana the road is now open from a transition to intermittent and low intensity struggles such as we have seen in universities from the end of the 1990s to the present, to open large-scale mass struggles against the state.

These contradictions therefore produced two related but different movements. The first was the #RhodesMustFall movement, which began at the University of Cape Town.

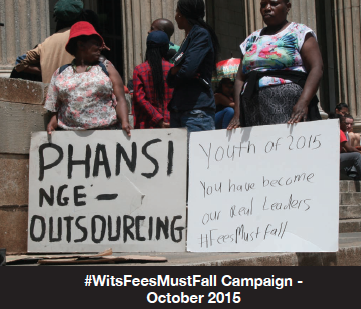

The second is the #FeesMustFall movement, which had been building up in the bush colleges for more than a decade but caught the public imagination around October 2015, when students shut down Wits University demanding that fee increases be cancelled. The first movement expresses the ideological and political nature of the crisis facing the black middle class more clearly. Its main focus is on the issue of black advancement within the institutions of higher learning. In that movement (its Manifesto is included in this edition) the focus is on the barriers faced by black students, and also by implication, black academics in institutions of higher learning that are historically white and represent the wealthy classes in society.

The second is the #FeesMustFall movement, which had been building up in the bush colleges for more than a decade but caught the public imagination around October 2015, when students shut down Wits University demanding that fee increases be cancelled. The first movement expresses the ideological and political nature of the crisis facing the black middle class more clearly. Its main focus is on the issue of black advancement within the institutions of higher learning. In that movement (its Manifesto is included in this edition) the focus is on the barriers faced by black students, and also by implication, black academics in institutions of higher learning that are historically white and represent the wealthy classes in society.

The second movement also expressed the challenges of the black middle classes, but also intersected with the challenges facing the working class’ access to higher education. For this reason, because of this intersection of the direct interest of the working class, the #FeesMustFall movement is the first in what is likely to be a series of social and political struggles in the terrain of education in South Africa. Like the struggles of students in the 1980s, these struggles will most likely intersect with the broader interests of the working class – an intersection that in this specific wave of the student struggle was deflected by the high-profile presence of Wits University as a key driver of this struggle, at least in the press and therefore the public imagination.

Forty years on: What are the Challenges Facing Students?

While everybody accepts the fact that present day and future struggles will not be the same as those of 1976 and the 1980s, the forty years of student struggles since 1976, and in particular the significant body of experience of struggle in the post-apartheid period provides students today with an opportunity to learn from struggles waged by the classes of 1976, and indeed that of the1980s.