“Plans together for after work today. Today today today. Take destiny in our? False hopes. Today. Plans to attend. Plans to attend to. Plans assembling in her mind on her mop. They’ve had enough of it…”

“Plans together for after work today. Today today today. Take destiny in our? False hopes. Today. Plans to attend. Plans to attend to. Plans assembling in her mind on her mop. They’ve had enough of it…”

Getting Rid Of It was written by Lindsey Collen and published in 1997 by Granta Book (London). Collen’s second novel is set in Mauritius, and narrates the events that take place within one day for the three protagonists, Sadna, Goldilox Soo and Jumila. But within this single day, the narrator shares with us these three young women’s thoughts, feelings, memories.

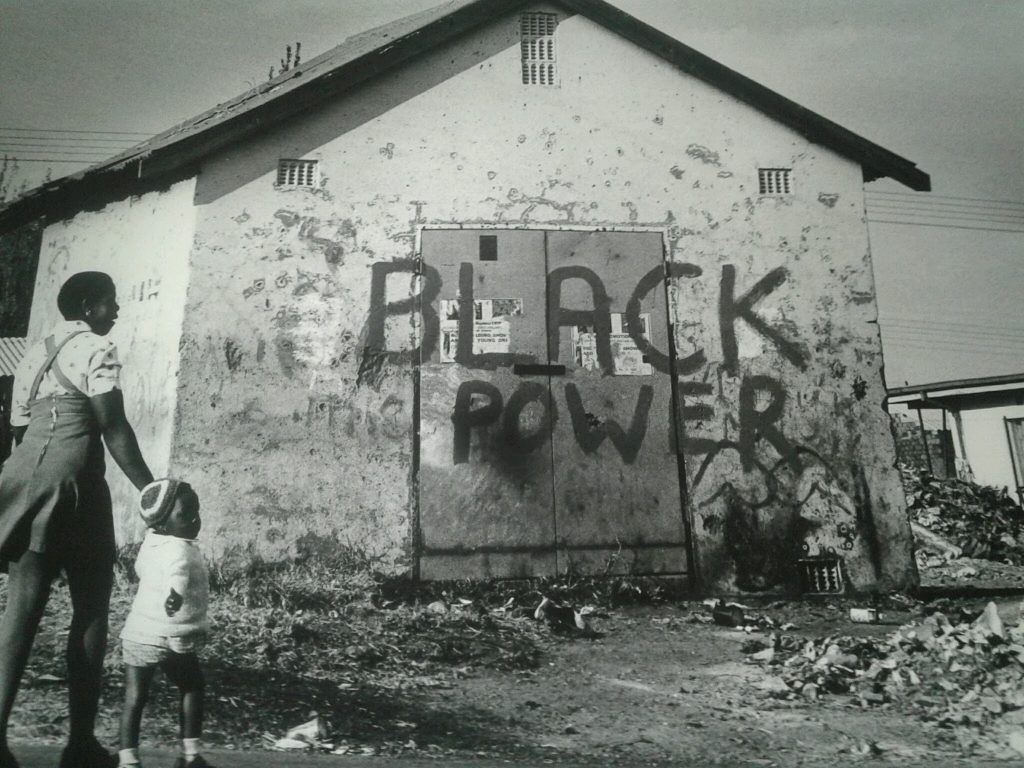

Goldilox Soo works for a cleaning company as a ‘piece-rate girl’, Jumila is a vendor who sells bras at a local market and Sadna works at a hospital as a cleaner. All these young women meet each other as neighbours in the same informal settlement, Kan Yolof, and learn that they have more in common than they thought. By taking us into the lives and pasts of these three women, we begin to piece together the many threads that connect and bond them together, all leading up to their collective decision to collectively act and change their circumstances.

But their plans are disrupted by matters that often only affect women. Jumila suffers a late miscarriage of a pregnancy she was unaware of, and because the law works against women in such situations, often criminalising and imprisoning them, Jumila seeks help from the other two in resolving the matter without trouble. Getting Rid Of It puts into sharp focus the tragedies many women endure in a patriarchal society and the struggles women face for control over their own bodies, and their reproductive rights.

The novel highlights the absurdities and strangeness of life, through the use of old Mauritian myths and fairy tales interwoven with the experiences and histories of these women, and the women they encounter. Getting Rid Of It is dinstinctly Mauritian, as Collen depicts the vibrant culture, the beautiful landscapes of the island, and its harsh history, sometimes using Mauritian Kreole to do so.

But although published 20 years ago, and written in the particular context of Mauritian society, it is disturbingly relevant to South African society today, and women, particularly black women’s position within it. Although women’s right to choose is a victory hard-won in South Africa, very few enjoy these rights that are meant to guarantee safe, accessible and free medical care. Domestic violence, femicide, rape and rape culture continue to remain apart of black women’s daily reality. It is too often fatally dangerous to be a woman or girl, in the home and in the public sphere in contemporary South Africa.