40 years later, legendary photographer, Peter Magubane, once again brings to life the Soweto 1976 youth uprising. The photo exhibition, commemorating most appropriately the 40th anniversary of Soweto 1976, was opened on Sunday, 5 February, at CameraZ Gallery, in Rosebank Mall, Johannesburg.

Peter Magubane is a photo-journalist who was born in 1932 in Vrededorp in Johannesburg, and who grew up and completed high school in Sophiatown. His interest in photography began with his first Kodak brownie camera. Magubane pursued his interest in photography at Drum magazine where he started in 1954 as a driver and a messenger. Later he worked for the chief photographer, Jurgen Schaderberg, as his dark room assistant. By 1961 he held his first photography exhibition, one of the first black photographers to do this.

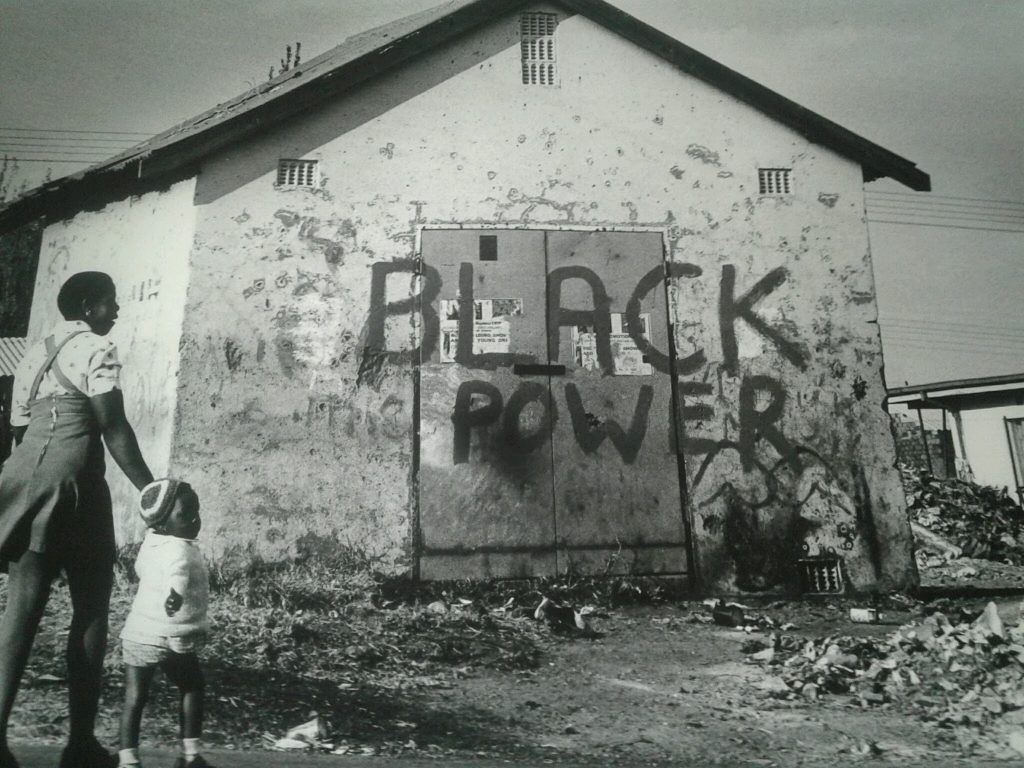

The current exhibition, a series of black and white photographs, is a tribute to the Soweto uprisings that stays with one for a long time. “My work speaks for itself”, said a frail, white-haired Magubane, who was present at the exhibition opening. Indeed, the photos throw even more light on 1976; the horrors of apartheid, but also the passion, commitment and energy of youth in this country, and in the liberation struggle. The photos are poignant: youth smiling and laughing as they demonstrate, women searching amongst the dead for loved ones, a newspaper cover revealing the slim fingers of a human hand.

During the Soweto uprisings Magubane worked for the Rand Daily Mail. He was assaulted by police (a photo in the exhibition), because he refused to expose his camera film to the light. Detained many times in the 1970s, he was also kept in solitary confinement for a long period of time. In 1976 he convinced students to let him take photos. “You can’t have a struggle if you don’t document it”, Magubane said.

During the Soweto uprisings Magubane worked for the Rand Daily Mail. He was assaulted by police (a photo in the exhibition), because he refused to expose his camera film to the light. Detained many times in the 1970s, he was also kept in solitary confinement for a long period of time. In 1976 he convinced students to let him take photos. “You can’t have a struggle if you don’t document it”, Magubane said.

The exhibition is wrenching as it raises starkly the current realities of South Africa, a country significantly marked by social inequality and poverty. It was difficult to remain dry-eyed as the photos bring the people to life, exercising their agency, the struggles, the memories and South Africa today, now! The continuity with contemporary struggles 40 years later is distressing. ‘Why are students betrayed?’ reads one of the placards in the exhibition, foretelling #FeesMustFall in 2015.

The social inequality was even more accentuated by the opulence of Rosebank Mall and the predominantly white audience. And it was interesting to note one of the speakers, Murphy Morobe, suggesting that the ANC NEC meet in the midst of this exhibition, to remind themselves of what the project for liberation was all about.

This powerfully haunting exhibition should travel the length and breadth of this country.