Working class communities are gripped by differences and a debate about the role of money in romantic relationships between partners. During the session facilitated by Nosipho Mdletshe of Khanya, each of the speakers was given three minutes to make their opening speeches. The motion was whether a man should pay a girlfriend allowance, also termed ‘ukubheja’, a Nguni word derived from the English, ‘to bet’.

To bheja is a notion that argued that women should receive a girlfriend allowance to main their beauty, the allowance covers the cost of toiletries, make-up, hair and clothes because, in a relationship, you have certain expectations and desire for your partner to appeal to you. Some argue against this practice because they feel like it is the same as paying for love. The teams shared arguments that unpacked the economics of love in working class relationship dynamics.

The first speaker from the team in favour of the motion, Tshepang Sesoane from the Kliptown Youth Program argued “I believe in the notion of to bheja because it is an act to show support to your partner. It is gender neutral since it also occurs in heterosexual and homosexual relationships therefore we cannot say it comes from a man to benefit a woman and it is even egalitarian because it’s sharing equally with your partner. We bheja to express gratitude for our loved ones, to appreciate them, and sometimes we show financial support especially when the other party is not employed it is not illogical for one to spoil their other half in a manner they deem fit without any expectations in return.’

Sesoane was followed by Bonolo Phohleli representing the team opposing the motion. Phohleli defined the word bhejaas “a sum of money you have to pay for expenses,” and added, “It is like a salary you [you earn but] did not work for.”

Phindezwa Tose said, “It is appreciation, support, and kindness. You cannot let your partner [to] suffer while you can see there is a problem somewhere,” she stated as added to the argument about what bheja is. The opposing team took it a notch up when Tebogo Tsweu from Best Health Solutions said that the practice aided gender-based violence because men who give their partners money and buy them things usually feel entitled to their bodies and often respond with violence where they cannot have things their way. This argument was elaborated by Busisiwe Ndzakayi from IKORA, an organisation from the Eastern Cape. She said, “It has the employer-employee kind of vibes…the one paying may be bossy [and] demand” service from the one receiving payments. She also dispelled the notion that the ‘girlfriend allowance’ was about support but that it funded luxuries the recipient could not afford and yet wanted.

This argument received support from the floor when Stephen Maciko, also participating in the workshop said, “It [to bheja] has an element of undermining women, you are like a sex worker, but you are not employed.”

Other speakers from the floor, including men, supported the notion that partners should receive financial benefits. Crosby Moatse said love is an action, which meant getting gifts for his partner.

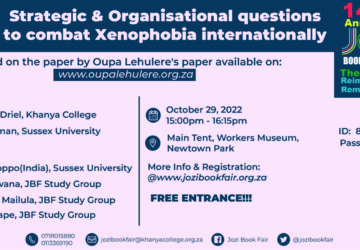

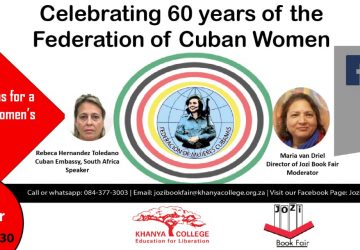

Comrades from Khanya mostly stood against the motion. Tsepiso Raseboku together with Searatoa Van Driel and Director, Maria Van Driel, all saw the practice as indicating a problem of poverty at its core, and also a need for more possessions even for middle-class women. Other speakers, including Noluvuyo Lata, linked the idea to lobola (dowry) as agents of violence against women in South Africa.

After comrade Maria Van Driel asked if the bheja practice ever takes place where there is no sex involved in the relationship, Sesoane argued that in romantic relationships between asexual people, the practice still existed. Although other speakers laboured to differentiate bheja from girlfriend allowance which they said was not voluntary, the two ideas were constantly mashed together throughout the debate. There was a visible difference in attitude to the bheja between the older generation and the younger. Jo-Anne Johannes (55), of Women on Farms, with Matheko Mohobo, another member of her organisation, both questioned if women who demanded bheja had the skills and means to build their own households and be taken seriously. The debate ended with a vote, with most people taking a stand against it although many also admitted they either practiced the bheja or accepted it from a romantic partner.

This article was submitted on 27 July 2023. You may republish this article, so long as you credit the authors and Karibu! Online (www.Karibu.org.za), and do not change the text. Please include a link back to the original article.

Download PDF

Download PDF